- Home

- Pat Conroy

My Losing Season

My Losing Season Read online

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Team Photo

Prologue

PART ONE

THE POINT GUARD TAKES TO THE COURT

1 Before First Practice

2 First Practice

3 Auburn

PART TWO

THE MAKING OF A POINT GUARD

4 First Shot

5 Gonzaga High School

6 Beaufort High

7 Plebe Year

8 Camp Wahoo

9 Return for Senior Year

10 Clemson

11 Green Weenies

12 Old Dominion

PART THREE

THE POINT GUARD FINDS HIS VOICE

13 New Orleans

14 Tampa Invitational Tournament

15 Columbia Lions

16 Christmas Break

17 Jacksonville to Richmond

18 Davidson

19 Furman Paladins

20 Annie Kate

21 Starving in Utopia

22 William and Mary

23 VMI

24 Four Overtimes

25 East Carolina

26 Orlando

27 Lefty Calls My Name

28 The Tournament

29 Ex–Basketball Players

PART FOUR

THE POINT GUARD’S WAY OF KNOWLEDGE

30 New Game

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

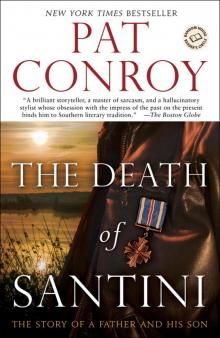

Excerpt from The Death of Santini

About the Author

ALSO BY PAT CONROY

Praise for MY LOSING SEASON

Copyright Page

This book is dedicated to my teammates on the 1966–67 Citadel

basketball team. It was an honor to take to the court with you guys.

Dan Mohr

Jim Halpin

John DeBrosse

Doug Bridges

Dave Bornhorst

Robert Cauthen

Bill Zycinsky

Alan Kroboth

Tee Hooper

Gregory Connor

Brian Kennedy

And their lovely wives and children who made me welcome in their homes: Maria, Alexis, and Michael Bornhorst; Sandra, Rob, Macon, and Buffy Cauthen; Eileen, James, and Michael Halpin; Cynthia, Micah, and Erin Kennedy; Teena, Doug, and Guy; Barbara, Gregory, Jeffrey, and Jeremy Connor; Cindy, Matthew, and Elizabeth Mohr; Pam, J.J., Scott, and Katie DeBrosse; Sherry, Travis, and Amy Hooper; Patty and George Kroboth.

And to my wife, Cassandra King, the light of my life.

* * *

* * *

THE CITADEL BASKETBALL SQUAD

1966-1967

* * *

* * *

FRONT ROW: John DeBrosse, Pat Conroy, Jim Halpin,

Tee Hooper

BACK ROW: Doug Bridges, Greg Connor, Brian Kennedy, Dave Bornhorst, Dan Mohr, Al Kroboth,

Bob Cauthen, Bill Zinsky

PROLOGUE

I WAS BORN TO BE A POINT GUARD, BUT NOT A VERY GOOD ONE.

There was a time in my life when I walked through the world known to myself and others as an athlete. It was part of my own definition of who I was and certainly the part I most respected. When I was a young man I was well built and agile and ready for the rough-and-tumble of games, and athletics provided the single outlet for a repressed and preternaturally shy boy to express himself in public. Games allowed me to introduce myself to people who had never heard me speak out loud, to earn their praise without uttering a single word. I lost myself in the beauty of sport and made my family proud while passing through the silent eye of the storm that was my childhood.

Football and baseball were always secondary sports to me, and I played them to appease my father, and because they were seasonal in nature. I tried out for baseball teams when farmers were planting cotton, and I was putting on a football helmet to run back punts when they were harvesting it. But I was a basketball player, pure and simple, and the majesty of that sweet sport defined and shaped my growing up. I cannot explain what the sport of basketball meant to me, but I have missed it more than anything else in my life since it issued me my walking papers and released me to live out my life as a voyeur and a fan. I was never a very good player, but the sport allowed me glimpses into the kind of man I was capable of becoming. I exulted in the pure physicality of that ceaseless, ever-moving sport, and when I found myself driving the lane beneath the hot lights amid the pure electric boisterousness of crowds humming and screaming as a backdrop to my passion, my chosen game, this love of my life, I was the happiest boy who ever lived.

Where did all those games go, the ones I threw myself headlong into as a boy, a rawboned kid who fell in love with the smell and shape of a basketball, who longed for its smooth skin on the nerve endings of my fingers and hands, who lived for the sound of its unmistakable heartbeat, its staccato rhythms, as I bounced it along the pavement throughout the ten thousand days of my boyhood? The one skill I brought to the game was my ability to handle a basketball, and if you tried to intercept me, if you moved without stealth or cunning, I would go past you. Even now that is a promise; I would pass you in a flash the entire game with you trying to catch me. I could move down the court with a basketball and I could do it fast.

But the games are fading on me now where once they imprinted themselves, bright as decals, on the whitewashed fences of memory. Once, I could replay them all, almost move for move, from the moment the referee first lofted the ball between the two crouching centers until the losing team launched their desperate, last-second shot, the horn sounded, and the players shook hands and drifted toward locker rooms and the judgment of our coaches. Yet, a few of those lost games maintain their power to thrill me with their immediacy and import. They take me back to a time when my life was pure action and my days passed among slashing elbows vying for rebounds coming off a clear glass backboard. Every practice and game contained the possibility of bones being broken. From the time I was nine until the day I left college, my knees stayed scabbed and tender from my scrambling for loose balls.

Because I was shorter than most college players, I tried to rule those lower regions, and when the ball hit the floor, it was mine, and too bad for you if you got in my way. I liked to put the big men on the floor when they fought me for possession of the ball as it was bouncing or rolling along the court. I substituted hustle for talent and the sure knowledge that if I did not want it more than my opponent, he would defeat and humiliate me with those gifts that nature denied me. What I had was a powerful will and a fiery competitiveness and the burning desire to be a great player in the Southern Conference when there was not even the slightest chance I could be a memorable one. I found myself constantly downsizing my dreams as a basketball player as my career was train-wrecked by mediocrity. But make no mistake, I desired greatness for myself and longed to be the best point guard who ever played the game.

From my ninth to my twenty-first year, I lived with a basketball in my hand, driving my mother crazy by throwing up imaginary jump shots in every room in the house. For years, I would try to take three hundred jump shots a day to improve my weakness as an outside shooter. I never left the court in my life after practice without making my last shot. This was not a superstition; this was a discipline.

The lessons I learned while playing basketball for the Citadel Bulldogs from 1963 to 1967 have proven priceless to me as both a writer and a man. I have a sense of fair play and sportsmanship. My work ethic is credible and you can count on me in the clutch. When given an assignment, I carry it out to completion, my five senses lit up in concentration. I believe with all my heart that athletics is one of the finest preparations for most of the intricacies and darknesses a human life can throw at you. Athletics provide some of the ri

chest fields of both metaphor and cliché to measure our lives against the intrusions and aggressions of other people. Basketball forced me to deal head-on with my inadequacies and terrors with no room or tolerance for evasion. Though it was a long process, I learned to honor myself for what I accomplished in a sport where I was overmatched and out of my league. I never once approached greatness, but toward the end of my career, I was always in the game.

Because I grew up a complete stranger to myself, I did not even seem to catch a glimpse of a determined young man who developed in secret during college. I do not recognize the intense stranger who stares back at me in photographs faded and frayed around the edges. My coaches, throughout my youth, all approved of me because my attitude was upbeat and fiery, my enthusiasm contagious, and I gave everything I had. I liked that part of me also but had no idea where it came from.

As a boy, I had constructed a shell for myself so impenetrable that I have been trying to write my way out of it for over thirty years, and even now I fear I have barely cracked its veneer. It is as rouged and polished and burnished as the specialized glass of telescopes, and it kept me hidden from the appraising eyes of the outside world long into manhood. But most of all it kept me hidden and safe from myself. No outsider I have ever met has struck me with the strangeness I encounter when I try to discover the deepest mysteries of the boy I once was. Several times in my life I have gone crazy, and I could not even begin to tell you why. The sadness collapses me from the inside out, and I have to follow the thing through until it finishes with me. It never happened to me when I was playing basketball because basketball was the only thing that granted me a complete and sublime congruence and oneness with the world. I found a joy, unrecapturable beyond the realm of speech or language, and I lost myself in the pure, dazzling majesty of my sweet, swift game.

After a Citadel baseball game at West Virginia where I hit a double, I came to a decision that would change my life. I was reading in the back of a station wagon that trailed two other cars full of sleeping baseball players, watching the moonlight snakehandle a mountain river. The moon felt different to me in the mountains as though my South traded it in for a different model when it reached the high country. Two songs came on the radio and I can hear them now as I write this. The river and the music and the moon came together in the mountains of West Virginia as the Mamas and the Papas sang “Monday, Monday.” Sarah Vaughan followed, singing a song that began with the words “How gentle is the rain.” I had never heard Sarah Vaughan sing before and rarely heard a voice that affected me like hers. Coming down that mountain, the radio playing songs perfect for that light-dazzled moment and the boys sleeping around me, I promised myself I would try to become a writer, though I did not know what one was or how they lived or how to go about being one. It was what my mother had always wanted me to become, but I never realized how powerful a mother’s dream could be to a dutiful, even worshipful, son. I made a secret pact with myself, in the dark; the music and river had awakened something asleep and I felt the writer stirring inside me for the first time. Once I woke him, I was never able to put him back to sleep in the porches of consciousness. In terror at what I had promised, I looked at the moon out of the back window as I watched West Virginia slip from my life forever.

During that same baseball season, I got my chance to share that small-craft epiphany I had experienced in the mountains. After a long road trip playing the small colleges of Georgia, the team was returning to Charleston at night. Chal Port was driving and I was riding in the front seat, which was something of a rarity. “Conroy,” he once asked me, “how come you got all the goddamn answers and no goddamn hits?”

Chal Port was the best coach I ever had, and his love of his boys poured out of him the way it always does with the best of the breed. On this night, Coach Port turned serious and asked us what we planned to do for a living after graduation. His roll call echoed through the car. John Warley would become the lawyer he is today in Richmond, Virginia. Holly Keller would take over his father’s piano store in Orlando, Florida. Mike Steele would enter the Army and rise higher and faster than anyone in my class; today he is a three-star general commanding the armies of the Pacific in Hawaii.

“What are you going to do, Conroy?” Chal Port asked. “Overthrow the elected government of the United States and all our allies?”

“I’m going to be a writer, Coach,” I said.

I still hear the laughter in that car.

“No. No. Come on, Conroy. You’ve got to think about making a living. What’re you really going to do?”

“I’m going to write books,” I said.

Again, the laughter settled in around me—on that flat Georgia road heading toward the Savannah River and the South Carolina line, I had suffered for my art for the first time, and red-faced, I joined in the mirth and hoopla at my own expense. It was my first moment of complete honesty at The Citadel, and it began my happiest year ever. As a senior private in Fourth Battalion in Romeo Company, I became untouchable and proud. The boys who had tormented me as a plebe had all left campus to play out their mediocre and mean-spirited lives. No longer did my blood boil when I passed some minor-league sadist on the way to the library. I grew relaxed as a cadet for the first time and almost fell to my knees in gratitude to my college for being the first place I had ever spent four uninterrupted years. Since my birth, I had moved twenty-three times, and The Citadel and the hauntingly beautiful city of Charleston had given me a sense of security and belongingness I had never known before. As an English major, my job and purpose in life was to read the greatest books ever written by the most fabulous and imaginative writers. I felt a sense of bedazzled guilt that I loved my courses and teachers so much and could not wait to get to my classes each morning.

It was the year I began to catch small glimpses of the man I was becoming, moments when all the disfigurements and odd bafflements of my hidden childhood began to reveal themselves in unfocused glances into my nature. In this last year I would play organized basketball I came into my own as a player, not because of my team’s success, but because of its crushing disappointments and failures. The season turned out to be a disaster for all concerned, except for me. I played the best basketball I ever played in the last half of what all remember as a jinxed and unprovidential season.

When I left The Citadel, I did not keep up with a single teammate from my losing season. It is the winners who have reunions, who stay in touch and whose wives and children know each other and gather together on those numerous occasions when their husbands and fathers try to recapture the uncommon glory they once felt when they were young athletes. The losing teams of the world disband without fanfare or any sense of regret. The names and faces of our teammates nick us like razors and recall moments of failure, disillusionment, disgrace. Losing tears along the seam of your own image of yourself. It is a mark of shame that causes internal injury, but no visible damage. The stigmata of that long-ago season have hurt me; I had let my team and my school down by not being good enough. As a basketball player, I always felt like a fraud and that same feeling has followed me into the writing life.

Yet I wish to be clear. I have loved nothing on this earth as I did the sport of basketball. I loved to break up a full-court press as much as anyone who has ever lived and played the game, black or white, male or female, in the shades of Spanish moss, beneath the roiled heat and sunshine of Dixie. I would not sell my soul to be playing college ball somewhere in this country tonight, but I would give it long and serious consideration. It was only when I had to give up basketball that I began to attract the unfavorable attention of the rest of the world. Basketball provided a legitimate physical outlet for all the violence and rage and sadness I later brought to the writing table. The game kept me from facing the ruined boy who played basketball instead of killing his father. It was also the main language that allowed father and son to talk to each other. If not for sports, I do not think my father ever would have talked to me.

I WOULD NOT

HAVE RETURNED TO this year of 1966 if I had not experienced one of those life-changing encounters on the road that rise up periodically to let us know that fate remains inexorable in its utter strangeness and its capacity for astonishment.

At a bookstore called Books & Co. in Dayton, Ohio, during my long tour for Beach Music, the first novel I had published in nine years, I looked up after signing my last autograph and I saw a man looking uncomfortable among the new novels published that season. Though I had not seen John DeBrosse in nearly thirty years, I recognized him immediately and felt that rush of pleasure one gets when encountering a part of the past that seemed irretrievably lost. When we had played together on the Citadel basketball team, John had always looked upon my love of reading as a form of mental illness. It amazed him I read books for pleasure and not because professors made me. I had once coveted and admired John DeBrosse’s game; I had the capacity to hero-worship all the boys who could play basketball better than I could, and my house of worship was large indeed. John DeBrosse was a player who started every game on every team he had ever played on, and he could shoot a basketball as well as the good ones. He was as serious as calculus and played basketball with the same devotion that monks often display at lauds or matins.

I was nearing my fiftieth birthday when John DeBrosse emerged from his own life in the fevers and agues of his own time in Ohio to find me. I rose up from the signing table to approach him, and we embraced.

“Ever been in a bookstore before, DeBrosse?”

“Yeah, once, Conroy. I was lost,” John said. “Hey—my wife and kids don’t think I know you. They think I made it all up. Could you come over to my house to meet them?”

John drove me toward his house in his huge van, very Ohio to me. We talked easily about guys we had known at The Citadel, but my information was fresher and far more up-to-date since Citadel men have always bought far more of my books than any other single group, and I had run into scores of them on the Beach Music tour. Then John’s conversation moved back toward memory and basketball. He had spent his whole life as a basketball coach, teacher, and principal in the Dayton area near his hometown of Piqua, Ohio. An educator of that most solid sort—the ones who make for consistency and excellence in our nation’s public schools—he embodied the Ohio virtues: his life was smooth and cautious and his prose was boilerplate. Put a man like John DeBrosse on guard duty, and he would issue a challenge to everything that went bump in the night.

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son

The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son The Boo

The Boo The Prince of Tides

The Prince of Tides Beach Music

Beach Music The Water Is Wide

The Water Is Wide My Losing Season

My Losing Season The Lords of Discipline

The Lords of Discipline Pat Conroy Cookbook

Pat Conroy Cookbook My Reading Life

My Reading Life My Exaggerated Life

My Exaggerated Life The Pat Conroy Cookbook

The Pat Conroy Cookbook A Lowcountry Heart

A Lowcountry Heart The Death of Santini

The Death of Santini