- Home

- Pat Conroy

My Reading Life

My Reading Life Read online

ALSO BY PAT CONROY

The Boo

The Water Is Wide

The Great Santini

The Lords of Discipline

The Prince of Tides

Beach Music

My Losing Season

The Pat Conroy Cookbook: Recipes of My Life

South of Broad

Copyright © 2010 by Pat Conroy

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Toronto.

www.nanatalese.com

Doubleday is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc. Nan A. Talese and the colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This page constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

Drawings by Wendell Minor

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Conroy, Pat.

My reading life / Pat Conroy. —1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Conroy, Pat—Books and reading. I. Title.

PS3553.O5198Z467 2010

813′.54—dc22

{[B]}

2010024309

eISBN: 978-0-385-53384-3

v3.1

This book is dedicated to my lost daughter,

Susannah Ansley Conroy. Know this: I love you

with my heart and always will. Your return

to my life would be one of the happiest moments

I could imagine.

CONTENTS

Cover

Other Books by This Author

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

CHAPTER ONE

THE LILY

CHAPTER TWO

GONE WITH THE WIND

CHAPTER THREE

THE TEACHER

CHAPTER FOUR

CHARLES DICKENS AND DAUFUSKIE ISLAND

CHAPTER FIVE

THE LIBRARIAN

CHAPTER SIX

THE OLD NEW YORK BOOK SHOP

CHAPTER SEVEN

THE BOOK REP

CHAPTER EIGHT

MY FIRST WRITERS’ CONFERENCE

CHAPTER NINE

ON BEING A MILITARY BRAT

CHAPTER TEN

A SOUTHERNER IN PARIS

CHAPTER ELEVEN

A LOVE LETTER TO THOMAS WOLFE

CHAPTER TWELVE

THE COUNT

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

MY TEACHER, JAMES DICKEY

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

WHY I WRITE

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

THE CITY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

About the Author

CHAPTER ONE

THE LILY

Between the ages of six and nine, I was a native son of the marine bases of Cherry Point and Camp Lejeune in the eastern coastal regions of North Carolina. My father flew in squadrons of slant-winged Corsairs, which I still think of as the most beautiful warplanes that ever took to the sky. For a year Dad flew with the great Boston hitter and left fielder Ted Williams, and family lore has it that my mother and Mrs. Williams used to bathe my sister and me along with Ted Williams’s daughter. That still remains the most distinguished moment of my commonplace career as an athlete. I followed Ted Williams’s pursuit of greatness, reveling in my father’s insider knowledge that “Ted [has] the best reflexes of any marine pilot who ever flew Corsairs.” I read every book about baseball in the library of each base and town we entered, hoping for any information about “the Kid” or “the Splendid Splinter.” When the movie of The Great Santini came out starring Robert Duvall, Ted Williams told a sportswriter that he’d once flown with Santini. My whole writing career was affirmed with that single, transcendent moment.

The forests around Cherry Point and Camp Lejeune were vast to the imagination of a boy. Once I climbed an oak tree as high as I could go in Camp Lejeune, then watched a battalion of marines with their weapons locked and loaded slip in wordless silence beneath me as they approached enemy territory. When I built a bridge near “B” building in Cherry Point, I invited the comely Kathleen McCadden to witness my first crossing. I had painted my face like a Lumbee Indian and wielded a Cherokee tomahawk I had fashioned to earn a silver arrow point as a Cub Scout. My bridge collapsed in a heap around me and I fell into the middle of a shallow creek as poor Kathleen screamed with laughter on the bank. Though a failed bridge maker, I showed more skill in the task of the tomahawk and I felled Kathleen with a wild toss that deflected off her shoulder blade. My mother handled the whipping that night, so further discipline by my father proved unnecessary. For the rest of my life, I would read books on Native Americans and I once coached an Indian baseball team on the Near North Side of Omaha, Nebraska, after my freshman year at The Citadel. Pretty Kathleen McCadden never spoke to me again, and her father always looked as if he wanted to beat me. I was seven years old.

Yet an intellectual life often forms in the strangest, most infertile of conditions. The deep forests of those isolated bases became the kingdom that I took ownership of as a child. I followed the minnow-laced streams as they made their cutting way toward the Trent River. Each time in the woods, I brought my nature-obsessed mother a series of captured animals, from snapping turtles to copperheads. Mom would study their scales or fur or plumage as I brought home everything from baby herons to squirrels for her patient inspection. After she looked over the day’s catch, she would shower me with praise, then send me back into the woods to return my captives where I’d discovered them. She told me she thought I could become a world-class naturalist, or even the director of the San Diego Zoo.

At the library she began to check out books that gave me a working knowledge of those creatures that my inquisitive, overprotective dog and I had found while wandering the woods. When Chippie jumped between me and an eastern diamondback rattler and took a strike on the muzzle before she broke the snake’s back, my mother decided that I’d do my most important work in the game preserves of Africa with the scent of lions inflaming Chippie’s extraordinary sense of smell. By the time I had finished fifth grade, I knew the name of almost every mammal in Africa. I even brought her a baby fox once and had a coral snake in a pickle jar. She answered me with trips to the library, where I found a whole section labeled “Africa,” the books oversized and swimming with photographs of creatures with their claws extended and their fangs bared. Elephants moved across parched savannas and hippopotamuses bellowed in the Nile River; crocodiles sunned themselves on riverbanks where herds of zebra came to drink their fill. Books permitted me to embark on dangerous voyages to a world of painted faces of mandrills and leopards scanning the veldt from the high branches of a baobab tree. There was nothing my mother could not bring me from a library. When I met a young marine in the woods one day hunting butterflies with a net and a killing jar, my mother checked out a book that took me far into the world of lepidoptera, with hairstreaks, sulphurs, and fritillaries placed in solemn rows.

Whatever prize I brought out of the woods, my mother could match with a book from the library. She read so many books that she was famous among the librarians in every town she entered. Since she did not attend college, she looked to librarians as her magic carpet into a serious intellectual life. Books contained powerful amulets that could lead to paths of certain wisdom. Novels taught her everything she needed to know about the mysteries and uncertainties of being human. She was sure that if she could find the right book, it would reveal what was necessary for her to become a woman of substance and parts. She outread a whole generation of officers’ wives but still wilted in embarrassment when asked about her college degree. I was a teenager when I heard Mom claim that she had just finished her first year at Agnes Scott when she dropped out to marry m

y father. By the time I graduated from The Citadel, my mother was saying that she had matriculated with honors from Agnes Scott, with a degree in English. Though I feared the possibility of her exposure, I thought that the lie was harmless enough. Her vast reading provided all the armor she needed to camouflage her lack of education. At formal teas, she talked of Pasternak and Dostoyevsky. She subscribed to the Saturday Review, then passed it on to my sister Carol and me after she had read it from cover to cover. After Mom fell in love with John Ciardi, I checked out his translation of Dante’s The Divine Comedy. She spoke about the circles of Hell for the rest of her life. Even if Dante daunted and intimidated her, she cherished Eudora Welty and Edith Wharton and knew her way around the works of Hemingway and Fitzgerald. Whenever she opened a new book, she could escape the exhausting life of a mother of seven and enter into cloistered realms forbidden to a woman born among the mean fields of Georgia.

Peg Conroy used reading as a text of liberation, a way out of the sourceless labyrinth that devoured poor Southern girls like herself. She directed me to every book I ever read until I graduated from the eighth grade at Blessed Sacrament School in Alexandria, Virginia. When I won the Martin T. Quinn Scholarship for Academic Achievement, Mom thought she had produced a genius in the rough.

In high school, my mother surrendered my education up to the English teachers who would lead me blindfolded toward the astonishments that literature had to offer. In Belmont, North Carolina, Sister Mary Ann of the Order of the Sacred Heart taught a small but serious class in that Book of Common Prayer that makes up the bulk of a fourteen-year-old American’s introduction to the great writers of the world. It took me six months to fathom the mystery that my mother was copying out my homework assignments in an act of mimicry that made me pity her in some ways but admire her indefatigable trek toward self-improvement in others. It was a year my father made dangerous for me, and there was a strange correlation between his brutality and my reaching puberty that was then incomprehensible to me. It infuriated him when he found my mother and me discussing an Edgar Allan Poe short story or Ambrose Bierce’s “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge.” He found me showing off and vain. It marked the year my blue eyes began to burn with hatred whenever he entered a room. Though I tried, I could not control that loathing no matter what strategies I used. He would take me by the throat in that tiny house on Kees Road, lift me off my feet, strangle me and beat my head against the wall. When later I was living by myself in Atlanta in 1979, my father came to visit me after an extended visit with all his children. He recounted a story that my brother Jim had told him, and said, “Jesus, my kids can make shit up. Jim claimed that his first memory of you was me beating your brains out against some wall. Isn’t that hilarious?”

“I can show you the wall,” I said.

On the day Sister Mary Ann handed out copies of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, I understood at last that I was coming face-to-face with the greatest writer who ever lived. The strangeness of Elizabethan dialogue stymied me at first, but I was taking turns reading it with my mother, and noted her own puzzlement as we encountered a diction and elaborate phrasing that was unfamiliar to us. When Orsino opens the play with his famous declaration, “If music be the food of love, play on,” we were fine, but both of us were stopped in midsentence by a word unknown to us—“surfeiting.”

“Look it up, Pat,” Mom said. “If we don’t know a word, we can’t understand the sentence.”

I looked up the word and said, “You eat too much. You get too full.”

“Like the radio, if they play a song too much, you get sick of it. It happened to me with ‘Tennessee Waltz,’ ” she said.

The next stoppage of our kitchen performance took place when the servant Curio asked the duke if he would go hunting the “hart.”

“Maybe it’s a misprint,” Mom said. “What does it mean?”

“In England it’s a deer. A red deer,” I said, consulting the dictionary.

“Okay, the duke says that music is the food of love,” she said. “I got it. It’s a pun. A pun! The duke is in love, so he’s going to be hunting the human heart of a young woman.”

I’ve never been a great admirer of the pun, so I didn’t quite catch my mother’s drift because there lives a strange literalist inside me who swats away at puns as though routing a swarm of flies. It’s hard to take pleasure in something you don’t understand and in my own psyche, a “hart” could never pass for a “heart.” But looking back at the play I haven’t read for fifty years, it strikes me now that my mother was correct in her assessment of the Shakespearean world. For the rest of my high school and college career, she read every short story, poem, play, and novel that I read. I would bring notebooks home from The Citadel, and Mom would devour those of each literature course I took. Only after her death did I realize that my mother entered The Citadel the same day I did. She made sure that her education was identical to mine. She knew Milton’s Paradise Lost a whole lot better than I did.

In my junior year, she developed a schoolgirl crush on Col. James Harrison, who taught American literature. He filled his lectures with a refined erudition, a passion for good writing, and a complete dedication to the task of turning his cadets into well-spoken and clear-thinking young men. But Mom fell head over heels for the lovely man the day Colonel Harrison read the Whitman poem “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” With the softest of voices, he read to his class the poet’s moving elegy on the death of Abraham Lincoln. Halfway through his recitation, he confessed to us that he always wept whenever he read that particular poem. He apologized to the class for his lack of professionalism. He wiped his glasses and, with tears streaming down his face, he dismissed the class and headed toward his office. The grandson of a Confederate officer had been moved to tears by a poem commemorating the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. For me that day will last forever. I had no idea that poetry could bring a grown man to his knees until Colonel Harrison proved it. It ratified a theory of mine that great writing could sneak up on you, master of a thousand disguises: prodigal kinsman, messenger boy, class clown, commander of artillery, altar boy, lace maker, exiled king, peacemaker, or moon goddess. I had witnessed with my own eyes that a poem made a colonel cry. Though it was not part of a lesson plan, it imparted a truth that left me spellbound. Great words, arranged with cunning and artistry, could change the perceived world for some readers. From the beginning I’ve searched out those writers unafraid to stir up the emotions, who entrust me with their darkest passions, their most indestructible yearnings, and their most soul-killing doubts. I trust the great novelists to teach me how to live, how to feel, how to love and hate. I trust them to show me the dangers I will encounter on the road as I stagger on my own troubled passage through a complicated life of books that try to teach me how to die.

I take it as an article of faith that the novels I’ve loved will live inside me forever. Let me call on the spirit of Anna Karenina as she steps out onto the train tracks of Moscow in the last minute of her glorious and implacable life. Let me beckon Madame Bovary to issue me a cursory note of warning whenever I get suicidal or despairing as I live out a life too sad by half. If I close my eyes I can conjure up a whole country of the dead who will live for all time because writers turned them into living flesh and blood. There is Jay Gatsby floating face downward in his swimming pool or Tom Robinson’s bullet-riddled body cut down in his Alabama prison yard in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Hector can still impart lessons about honor as he rides out to face Achilles on the plains of Troy. At any time, night or day, I can conjure up the fatal love of Romeo for the raven-haired Juliet. The insufferable Casaubon dies in Middlemarch and Robert Jordan awaits his death in the mountains of Spain in For Whom the Bell Tolls. In Look Homeward, Angel, the death of Ben Gant can still make me weep, as can the death of Thomas Wolfe’s stone-carving father in Of Time and the River. On the isle of Crete I bought Report to Greco by Nikos Kazantzakis and still see the immortal scene when the author�

�s father took him to a devastated garden to witness the swinging bodies of Greek patriots hanging from the branches of fruit trees. In a scene that has haunted me since I first read it, the father lifted his son off the Cretan earth and made the boy kiss the bottom of the dead men’s feet. Though nearly gagging, the young Kazantzakis kisses dirt from the lifeless feet as the father tells him that’s what courage tastes like, that’s what freedom tastes like.

When Isabel Archer falls in love with Gilbert Osmond in The Portrait of a Lady, I still want to signal her to the dangers inherent in this fatal choice of a husband, one whose cunning took on an attractive finish but lacked depth. She has chosen a man whose character was not only undistinguished, but also salable to the highest bidder.

To my mother, a library was a palace of desire masquerading in a wilderness of books. In the downtown library of Orlando, Florida, Mom pointed out a solid embankment of books. In serious battalions the volumes stood in strict formations, straight-backed and squared away. They looked like unsmiling volunteers shined and ready for dress parade. “What furniture, what furniture!” she cried, admiring those books looking out on a street lined with palms and hibiscus.

I was eleven years old that year, and my brother Jim was an infant. Mom walked her brood of six children along the banks of Lake Eola on the way home to Livingston Street. My uncle Russ would leave his dentist’s office at five, pick up the books my mother had checked out for herself and her kids, and hand-deliver them on his way home to North Hyer Street. On this particular day, Mom stopped with her incurious children near an artist putting the finishing touches on a landscape illuminating one corner of the park surrounding the lake. She gazed at the painting with a joyful intensity as the artist painted a snow-white lily on a footprint-shaped pad as a final, insouciant touch. Mom squealed with pleasure and the bargaining began. From the beginning, the Florida artist Jack W. Lawrence was putty in my comely mother’s hands. Flirtation was less of an art form with her than it was a means to an end, or a way of life. Jack demanded fifty dollars for his masterwork and after much charming repartee between artist and customer, he let it go for ten.

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life

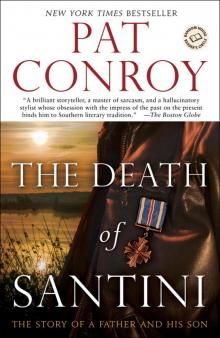

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son

The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son The Boo

The Boo The Prince of Tides

The Prince of Tides Beach Music

Beach Music The Water Is Wide

The Water Is Wide My Losing Season

My Losing Season The Lords of Discipline

The Lords of Discipline Pat Conroy Cookbook

Pat Conroy Cookbook My Reading Life

My Reading Life My Exaggerated Life

My Exaggerated Life The Pat Conroy Cookbook

The Pat Conroy Cookbook A Lowcountry Heart

A Lowcountry Heart The Death of Santini

The Death of Santini