- Home

- Pat Conroy

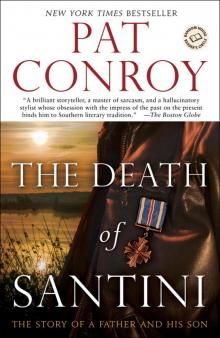

The Death of Santini Page 18

The Death of Santini Read online

Page 18

So my mother traveled north to Bethesda and disappeared among the oncologists of the navy and returned a week later and never mentioned her cancer to any of her children again. A couple of months after she returned I was driving my brother Tim to school one morning when he began weeping at a stoplight.

“What’s wrong, Timmy?” I asked, hugging his neck, his sobs out of control.

When he started breathing normally again, Tim looked at me and said, “Why isn’t she dead?”

“I don’t know, but I’m sure glad she isn’t,” I told my brother.

Now, fourteen years after Peg Conroy told her kids that she would be dead in two weeks from leukemia, she had leukemia.

• • •

The Conroy clan had begun to gather in earnest as I was flying across the Atlantic the next evening. When I saw my mother in a coma, I burst into tears. I sat on her bed and kissed her face and hands. From my point of view she looked as though she might die in the next minute. Empurpled from bruises all over her body, she resembled the survivor of a terrible car crash. I prayed as hard as I could and even found myself whispering the confiteor in Latin from my years as an altar boy. I spent the rest of that week in a state of shock, but the week proved fruitful, because the only subject on anyone’s lips was the life and hard times of Peg Conroy.

My brothers and sisters had all assembled, and my two aunts had shown up with Stanny a little before my own arrival—the cousinry would not disembark until the weekend. The entire family was shaken hard by Mom’s catastrophic condition. The Conroy humor, which could range from savage to boisterous, was nowhere to be found. My mother’s husband, John Egan, busied himself making phone calls to his own seven children, giving them twice-daily reports on my mother’s prognosis. He motioned for me to accompany him out to the hall. We embraced and he began weeping against my shoulder. Though it embarrassed him, it took several moments for him to compose himself.

“I need to ask you a question, Pat,” John said. “Could I have your permission to call your father? He was married to Peg for thirty-three years and I think he should be here.”

“That’s as nice a thing as I’ve ever heard,” I said.

“Do you think the other kids will mind?” he asked.

“I think they’re gonna love your ass forever,” I said, “Just like I will.”

Slowly and over time, the glacier that formed between my parents had begun to thaw as the years of their separation added up. Their children delivered reports from the front lines about both of them. Mom was particularly interested in the number of women my father was dating. Grandchildren were born to Jim and Janice, who lived then in Atlanta, as well as Kathy and her husband, Bobby Joe, who were still in Beaufort. Time passing has a soothing, ameliorative effect, and memory softens as its tides flow out to sea. And to the amazement of all his children, Dad was turning into a man of decency and self-control.

The news lifted us when once it would have dropped us into a lightless abyss. Dad’s rehabilitation of himself as a father was still a work in progress, but had inched along with such tortoiselike persistence that he had already established his reliability and steadfastness to his younger children. Unlike my penny-pinching mother, Dad was always generous with money where his kids and grandkids were concerned. In his retirement years, Dad had surprised himself and shocked his children by developing a terrific sense of humor. Of all the shameful things he did to us when we were kids, he never once made us laugh. When he entered the hospital waiting room, a cheer went up from the family and the Great Santini strolled into his element, shouting, “Stand by for a fighter pilot.” Our spirits soared as we moved to embrace our dad.

It was during that long vigil that I learned most of the stories of my mother’s early life—a subject I knew next to nothing about. I’d sit across from my aunts Helen and Evelyn, along with Stanny, as they talked about the early years in Rome, Georgia, and Piedmont, Alabama. All three of these women doctored their stories and memories with a flattering infusion of nostalgia and intentional blackouts when it came to the occasional murders, bootlegging, convictions, or out-of-wedlock babies.

Sister Kathy asked, “How did the family get to Atlanta? I’ve never heard that story.”

Since I knew Kathy had never heard “the creation myth” of our own family history, she didn’t understand the immediate emotional shutdown that made the three older women in the room voiceless as stones. Evelyn’s eyes flashed hatred at Stanny—Helen’s eyes moistened with hurt.

“Our mother abandoned us right in the middle of the Depression. She left four helpless children to fend for ourselves. There wasn’t no pie in the window when she left either,” Evelyn explained.

“I couldn’t throw a penny at a june bug ’cause I didn’t own one,” Stanny shot back. “I did what I thought I had to do, Evelyn. You’d have done the same thing if you were in my place.”

“I’d never leave my kids to starve to death,” Helen said. “Never. Those were terrible times.”

“It turned out well,” Stanny said to her grandchildren. “My girls all married military officers. My daughter had a movie made about her and the actress Blythe Danner played her. My son-in-law Don was played by Robert Duvall. My grandson Pat wrote the book The Great Santini. I became a world traveler and a hotelier of note in Monroe, Georgia. I’ve had a pretty good Southern life, if you ask me.”

Carol Ann said, “You had the heart of a giantess, Stanny. You were like the huntress Diana who went out tracking down her one true life. You were Odysseus trying to get back to your home after witnessing the unspeakable atrocities of war. You are the woman who freed my muse from the chains that the patriarchy enslaved women with for all these long centuries.”

“We get it, Carol,” Jim said.

“Message read loud and clear,” Tim said.

“It’s a wrap,” Mike added.

“Ah, the voice of the patriarchy!” Carol Ann mocked. “They try to silence me, but my voice can never be stilled because of your glorious break for freedom, Stanny.”

“It hurt our feelings, Carol Ann,” Helen said.

“It scared us to death. And I think it ruined your mother’s whole life. I really do,” Evelyn added.

With those dark words hanging in the air, I took my father down the long hallway to my mother’s room. As I opened the door, I said, “Hey, Dad, I’ll wait outside while you see Mom. Prepare yourself—she looks bad.”

“I’d like you to go in with me, Pat.” And so I did.

Dad gasped when he saw the graveness of her condition, then bent over and kissed her cheeks and forehead. He broke out his rosary blessed by the pope and we said a rosary for my mother’s recovery. As we returned to the waiting room, my father seemed to be in a state of unbearable shock.

“How’s Frances doing, Don?” Aunt Helen asked, reverting back to the name they called my mother as a child.

Mute as a streetlight, my father raised his right hand and put his arm straight out, his palm parallel to the floor. Then he slowly turned his hand over, simulating a jet plane going into a right-turning roll before going into a stall and falling out of the air on its way to a fiery crash when it met the earth. I used to see my father repeat that hand gesture whenever he described the fate of some fighter pilot who died in Korea. There were tears in Dad’s eyes that he tried to hide from the rest of us, but he was deeply shaken by the condition of my suffering mother.

As I sat in the hospital, I tried to figure out why we’d been to Piedmont only twice in all of my growing up. Except for her sisters and their children, no one with any Piedmont connection was present in the waiting room. Then it occurred to me that not a single relative of my father’s had arrived from Chicago to help my father in his grief, either.

Again, I returned to memory, and I thought hard about the visits I had made to the Conroy family seat in the heart of Irish Chicago on the South Side in St. Brendan’s Parish. The first unfortunate visit was when I was a toddler. I was a photogenic kid as an infant

, and I’m sure my mother expected to present her blond, smiling first grandchild born to the clan. Also, I have a strong belief that this was the first time my mother had met my grandparents or any of my aunts and uncles on the Chicago side. Most all of Dad’s siblings were still living at home in this cramped, wretched apartment house on Bishop Street.

I remember the attack on my mother with a strange vividness that still has the power to unsettle me.

I think it was Uncle Willie who said this first, but I can’t be sure: “Hey, Peggy, y’all want some grits for dinner? Lawdy, lawdy, they sho’ do love their grits, don’t they, girl-lee.”

A woman’s voice rang out: “Was yo’ raised by a mammy on a big plantation with yo’ slaves working in a cotton field?” That was my grandmother’s voice.

All this phony Southern slang unhinged my mother, and her discomfort level kept rising as the raucous, horse-laughing Irish pack closed in for the kill.

“We got you some Aunt Jemima pancake mix so y’all won’t feel homesick in the big city.”

Then rough hands reached out to tickle me and hurt me instead. In less than thirty seconds, Mom and I were both seeking comfort in each other’s arms. The city of Chicago, that brutish spitfire of a city, was lost to me forever that day, and I have met no one who has a stronger and more troubled relationship with being Irish than me. When I sign books in Chicago, the city’s Irish are open-armed and affectionate when they meet me and buy my books. They know my intimate ties to Chicago through my father, and always they ask me when I’m going to write a book about the Chicago Irish. It pains me to tell them I can’t, that I don’t know a single thing about the Irish Catholic in Chicago or my father’s people. I would have loved to write that novel, but the opportunity was stolen from me by a family that was hostile to strangers. I went back to the great city when I signed my book The Water Is Wide at the bookstore at Marshall Field’s, and realized what an incomparable loss the city of Chicago was for me.

As I sat there with my mother fighting for her life beside me, I thought about the uniqueness that shapes the destinies of all families. I visited the family seats of my two families only twice in my childhood, and both before I reached the first grade.

“I did not have a family,” I said to myself, startled I’d never noticed it before.

By the weekend, the cousins started to arrive. My cousin Carolyn was deeply inculcated with the religious fanaticism of my grandfather. In fact, Carolyn might be the holiest of holy rollers I’ve ever encountered in my circuits around the planet. Once at a book signing in Jacksonville, she was mumbling something in the stacks when the distraught owner came over and whispered to me, “Pat, we think there might be an assassin in the store.” He pointed to my cousin.

“No, sir. That’s my first cousin.”

“What’s she saying?” he asked.

“She’s speaking in glossolalia. You know, the unknown tongue,” I said.

“What the hell is that?” he asked.

“Don’t ask. Hey, Carolyn, how you doing?” I shouted out to her, and Carolyn answered back, “Hey, Conroy!”

A small line had formed at the table, and I was talking to several of my readers when I felt Carolyn’s hands enclosing my poor head. In her unknown tongue, Carolyn tried to remove the legion of demons who had taken possession of my immortal soul.

“Get your hands off my head, Carolyn,” I said.

“I’ve got amazing new powers you don’t know about. God has blessed me with the power to heal.”

Later, after she visited my mother at the hospital, Cousin Carolyn, who is always capable of spiritual surprises, took me aside and whispered to me about my mother’s condition.

“Lo and behold, I bring tidings of great hope,” Carolyn said. “Christ, the lord, has blessed me with new powers. Last week I raised a turtle from the dead.”

With the evangelicals of my mother’s family, I always found it problematic to enter into a comfort zone of conversation without it deteriorating into some form of shouting and testifying in a tent revival of the absurd. I considered the lucky turtle, then turned to my cousin and said, “Why?”

“To test these powers the almighty God has granted to me and to heal my fellow man,” Carolyn explained. “They’ve come just in time for me to raise your mama from the dead.”

“It couldn’t have come at a better time,” I assured her. “I’ll let the brothers and sisters know. They’ll be so relieved.”

An elegiac sweetness touched our vigil as the days drifted by and all the cousins gathered. We listened to the cautious reports issued by Mom’s doctor, Steve Madden, a handsome and exceptional oncologist who made us all feel confident that Mom was in good hands. He thought that Mom had a fair chance of surviving her coma, though he added that she could also die at any time. He recommended that we adopt an attitude of restrained hopefulness, and that if we were religious people, we should pray hard for her recovery. He need not have mentioned prayer, since there was more praying rolling out of that room than sweet iced tea from a local truck stop. Bible-thumping of a very high order was drumming the airways above the ten stories where we looked down to the parking lot below.

“Do you know that neither Mom nor Dad attended my graduation from college?” Jim said during one of our vigils. “What kind of family is that?” I think Jim was trying to cleanse the room of the roiling vapors of prayer and turn the subject back to his favorite topic—his contemptuous scorn for Mom and Dad as parents.

“Sounds like our family, Jim,” Mike said. “They missed my graduation too.”

“Same for me,” Tim said.

“Mom and the kids were at my Citadel graduation,” I said. “I think Dad was there.”

“No, Uncle Jim was there. That other flaming asshole from Chicago,” Mike said. “Dad took a rain check.”

“Hey, Carol,” Jim said, “did Dad go to your graduation?”

“No one went to my graduation,” Carol Ann said. “Not even my asshole brothers. Because I’m only a woman. The morning trash to the patriarchy. I grew up in the racist, unspeakable South, where women are just dirt.”

“I agree with her a hundred percent,” Tim’s new girlfriend, Terrye, chimed in. “From the things Tim has told me, I hate everything about a Conroy male,” she added.

Carol Ann answered by saying, “Five boys and two girls, Terrye. It made for a monstrous girlhood. Kathy and I were chattel slaves, devalued by our mother, unnoticed by our father, bullied to tears every night by the odious brother overlords.”

“Oh, yeah, Carol,” Mike said, “the only bully we produced was you, and the kid you bullied was me.”

“Amen,” said Jim.

“You were a jerk, Carol,” Tim added.

Carol Ann said to Terrye, “The rewriting of history is the true enemy of feminism. The male power structure selects a male with his jackboots on to write a text that makes women powerless or invisible. Even worse, it makes us witches or she-devils or banshees who need to be burned at the stake. I’ve played the role of Joan of Arc since the day I was born. My mother was always my greatest enemy. One day, I’ll write a poem describing this scene—my shallow, messed-up brothers trying to feign sadness when they’ve felt nothing of substance their whole lives.”

“Jim, you’re up next to stay an hour with Mom,” I said as I saw John Egan enter the room and walk over to my father to give him a report on Mom’s condition.

Over the ten days my family spent in Eisenhower, arguments and old grudges would flare; disappointments and hurts would take center stage, then retreat into alleyways of exhaustion as the different groups began to coalesce and join one another in the evening talks, where stories of Peg and Don were related by eyewitnesses like Aunt Evelyn, Stanny, our cousins, the Harper boys, and their mother, Aunt Helen. It was the first time the Conroy kids had ever heard the full rendition of Stanny’s mythic flight out of Egypt toward the bright lights of Atlanta, and the irreparable damage she had done to her children. But her defense of herself w

as rigorous as she pleaded for mercy from her two judgmental daughters. Aunt Evelyn said my mother’s departure frightened her so badly that she’d been afraid of everything for the rest of her life. She looked shaken as her children, nieces, and nephews heard her recitation of the story for the first time. I believe it was also the first time I saw Evelyn as a tragedy of a desperate white South, where the simple act of learning to read was revolutionary in nature. This was an ugly, morbid, unflattering South that my mother kept hidden from her children, just as she had refused to expose her kids to the rough-hewn Chicago where the grotesque Irish world of my father filled her with dread.

One day when Dr. Steve Madden came into the waiting room for his 11:00 p.m. consultation, he walked in with a springier step and then gave his hand away with a smile.

“I’m pleased to announce that Peg Egan is out of her coma and in remission. She passed her first great test of chemotherapy with flying colors.”

The shout that went up in that room would have awakened the entire hospital had it occurred at the midnight hour. We hugged one another and screamed out with relief. Even Carol Ann and I found ourselves hugging and me carrying her around the room.

Then Dr. Madden spoke again when the pandemonium eased up a bit. “I’ve given Peg something that will let her rest a couple of hours. Then I think she’ll be strong enough to entertain some short visits.”

Because I was heading back to Italy the next day, I was one of the first to visit Mom in her conscious state. It thrilled me to see her smile when I entered the room, and it pleased me that she had applied makeup and lipstick before she agreed to entertain visitors. When Mom wanted to be pretty for the world, it meant my girl was fighting back to her old self. Leaning down, I kissed her on both cheeks and began crying softly on her shoulder. She joined me in crying, and we held each other hard and long.

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son

The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son The Boo

The Boo The Prince of Tides

The Prince of Tides Beach Music

Beach Music The Water Is Wide

The Water Is Wide My Losing Season

My Losing Season The Lords of Discipline

The Lords of Discipline Pat Conroy Cookbook

Pat Conroy Cookbook My Reading Life

My Reading Life My Exaggerated Life

My Exaggerated Life The Pat Conroy Cookbook

The Pat Conroy Cookbook A Lowcountry Heart

A Lowcountry Heart The Death of Santini

The Death of Santini