- Home

- Pat Conroy

The Pat Conroy Cookbook Page 20

The Pat Conroy Cookbook Read online

Page 20

I was reading my note to Liz when one of her friends tapped me on the shoulder and said, handing me a plate, “You’ve got to eat this. It’s a Newberry County specialty. We call it Dunbar Macaroni.”

I had never seen Liz Norris after that day of Randy’s funeral. We would speak on the phone, but our paths never crossed again. As I ate Dunbar Macaroni for the second time in my life, I said a prayer for Liz, and thought how strange it was that her high school Harry had finally caught up with her when it was far too late for either one of us.

PICKLED SHRIMP When a good friend dies, I take two pounds of shrimp for the mourners. When a great friend dies, I go to five pounds. When I die, I fully expect all the shrimp in Beaufort to be pickled that day. • SERVES 6 TO 8

1 cup thinly sliced yellow onion

4 bay leaves, crushed

One 2-ounce bottle capers, drained and coarsely chopped

¼ cup fresh lemon juice

1 cup cider vinegar

½ cup olive oil

1 teaspoon minced fresh garlic

1 teaspoon coarse or kosher salt

1 teaspoon celery seeds

1 teaspoon red pepper flakes

2 pounds large (21-25 count) shrimp, peeled and deveined

1. Mix all the ingredients except the shrimp in a large heatproof glass or ceramic bowl.

2. In a medium stockpot over high heat, bring 4 quarts abundantly salted water to a rolling boil. Add the shrimp and cook until just pink, about 2 minutes. (The shrimp will continue to “cook” in the marinade.) Drain and immediately transfer to the marinade.

3. Bring to room temperature, cover tightly, and marinate overnight in the refrigerator. Transfer shrimp and marinade to a glass serving compote or bowl. Serve chilled.

CHEDDAR CHEESE COINS Cheddar cheese coins are the popular old Southern standbys cheese straws, but our recipe majored in economics. They are mouthwateringly good and a welcome addition to any Southern table at any time of the year. • MAKES 72

8 ounces extra-sharp orange cheddar cheese, grated (2 cups)

12 tablespoons (1½ sticks) unsalted butter, chilled but not hard

½ teaspoon cayenne pepper

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

2 cups unbleached all-purpose flour

1. Preheat the oven to 375°F.

2. In the bowl of a standing mixer, cream the cheese and butter until well combined. Mix the cayenne and black pepper into the flour. Add the flour mixture slowly to the bowl, stopping to scrape down the sides, until the mixture forms a ball.

3. Lightly flour a dry work surface and roll out the dough until ¼ inch thick. Using a 1½-inch straight-sided biscuit cutter, make the coins and transfer them to ungreased baking sheets. Reroll the scraps as needed.

4. Prick the top of each coin several times with the tines of a fork and bake until golden brown, about 15 minutes. Cool on a rack before serving.

FRESH HAM It is worth all the trouble in the world to fix a fresh ham. It is worth all the trouble in the world to fix fresh anything. I cannot think of ham without thinking of Southern funerals, and I do not believe I have ever eaten lunch after a funeral in the South without at least one ham there to feed the multitudes.

• SERVES A CROWD (AT LEAST 12 TO 14) WITH LEFTOVERS

1 large garlic head, cloves separated and finely chopped (about 5 tablespoons)

2 tablespoons dried thyme

2 tablespoons coarse or kosher salt

2 tablespoons freshly ground black pepper

One 16-pound fresh ham, skin on

1. Mix the garlic, thyme, salt, and pepper together in a bowl.

2. Place the ham in a large heavy roasting pan.

3. Cut 2-inch-long slashes in both sides of the ham and poke dozens of holes in it as well. Rub the salt mixture into the holes and over the outside of the ham. Let the ham absorb the seasoning for 1 hour at room temperature.

4. Preheat the oven to 450°F.

5. Roast the ham for 20 minutes at 450°F, then turn the oven down to 325°F. Cook for an additional 3½hours, until the internal temperature in the thickest part of the ham is 150°F and the skin is a burnished mahogany color. The skin will crisp to tasty cracklings.

6. Transfer the ham to a large platter, cover with aluminum foil, and let rest for 20 minutes so the juices will redistribute.

7. To carve, remove the skin and cut into strips for cracklings. Carve the ham into thin slices and serve.

DUNBAR MACARONI Dunbar Macaroni belongs to the town and history of Newberry, South Carolina. This is Julia Randel’s own personal recipe that she inherited from her mother, Mrs. Smith. I have seen several recipes that add ground beef or pork, but Julia insists that Dunbar Macaroni was meatless in its original, purest of forms. • SERVES 8 TO 10

1½ cups elbow macaroni

4 onions, chopped

Two 16-ounce cans whole tomatoes, preferably San Marzano, mashed, without their juice

¾ pound sharp cheddar cheese, grated

4 tablespoons (½ stick) butter

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

1. Preheat the oven to 350°F.

2. Cook the macaroni. Drain and set aside.

3. Cook the onions in 3 cups boiling water for 5 minutes. Drain. Add the tomatoes and cook over low heat for 10 minutes, until liquid has evaporated. Add the cooked macaroni, cheese, butter, salt and pepper. Mix together and pour into a large greased casserole dish.

4. Bake for 30 minutes, or until lightly browned. Serve hot.

COUNTRY HAM WITH BOURBON GLAZE

Now that I am older, I have eaten far too many slices of good country ham on biscuits in my lifetime at funerals too numerous to count. But this is the best recipe I know for anyone nervous around hams. Down here, when Southerners die, the pigs grow nervous.

• SERVES A CROWD (AT LEAST 12 TO 14) WITH LEFTOVERS

One 12- to 14-pound bone-in cured ham

½ cup apple juice

1 teaspoon ground cloves

FOR THE GLAZE

½ cup best-quality maple syrup

¼ cup bourbon

½ cup plus ¼ cup apple juice

1. Unwrap the ham and let it come to room temperature, at least 2 hours. This helps the ham absorb the liquid used in cooking, making the meat more flavorful.

2. Preheat the oven to 325°F.

3. Pull away most of the rind (in many cases, this has already been done) of the ham and trim the excess fat to an even ¼ or ½inch. Using a sharp knife, score the fat lightly in diagonal lines to create a diamond pattern. Put the prepared ham, fat side up, in a sturdy, shallow baking pan and place in the oven. Mix the apple juice and ground cloves with 1 cup water and pour into the pan. Bake for 1½hours.

4. To make the glaze: In a medium bowl, combine the maple syrup, bourbon, and ¼ cup apple juice.

5. Without removing the pan from the oven (just pull out the rack, provided it is sturdy enough), pour the glaze over the top of the ham. Add the remaining ½ cup apple juice to the pan and continue cooking for another 45 minutes, basting frequently. (You are looking for about 140°F on an instant-read meat thermometer.) Remove the pan from the oven and allow the ham to cool on a rack before carving and serving.

BISCUITS • MAKES 12

2 cups self-rising flour (preferably White Lily)

½ teaspoon salt

3. teaspoons baking powder

½ teaspoon baking soda

5 tablespoons cold unsalted butter, cut into 5 pieces

1 scant cup buttermilk

1. Preheat the oven to 450° F. Place rack in middle of oven.

2. In a large bowl, sift together the flour, salt, baking powder, and baking soda. Add the cold butter pieces to the flour and cut in with two knives (or rub butter into flour with your fingers). When the mixture resembles coarse crumbs the size of peas, pour almost all of the buttermilk in and stir with a wooden spoon just until dough forms one piece. If the dough doesn’t come together, add the remaining buttermilk.

/> 3. Turn the dough out onto a dry, lightly floured work surface. Using a wooden rolling pin, roll into a rectangle about ½inch thick. Use a biscuit cutter or the open end of a glass to cut rounds of dough.

4. Place the biscuits on an ungreased cookie sheet. The scraps of dough can be gathered and rolled again one more time. If not baking the biscuits immediately, cover them with plastic wrap and refrigerate for 2 to 3 hours.

5. Bake for 12 to 14 minutes or until lightly browned on top. Serve hot.

GRITS CASSEROLE This is the best grits casserole I have ever eaten. Grits provide an empty canvas for all kinds of experimentation. I have cooked the casserole using different kinds of cheese, thrown in a nugget of garlic or a ragout of wild mushrooms. Grits is a food that for gives almost any kind of messing around or tomfoolery by a cook. The best grits I have ever tasted come from Anson Mills out of Columbia, South Carolina. Of course, they are stone-ground. • SERVES 6

½ teaspoon coarse or kosher salt

1 cup slow-cooking stone-ground grits

½ pound andouille sausage, chopped

2½ cups grated sharp cheddar cheese

3 large eggs, beaten

¼ cup heavy cream

Tabasco sauce

Coarse or kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

1. In a large saucepan over high heat, bring 4 cups water to a boil. Add the salt and slowly pour in the grits. Reduce the heat and cook, stirring occasionally, until grits are done, about 40 minutes.

2. Preheat the oven to 350°F.

3. In a small saucepan, sauté the sausage until it is slightly crispy, 8 to 10 minutes. Set aside.

4. Remove grits from the stove and add the cheese, stirring until smooth. Beat in the eggs and cream. Add the sausage and season to taste with Tabasco and salt and pepper.

5. Pour the grits into a 2-quart soufflé dish and bake until they are set and lightly browned on top, about 40 minutes. Serve hot.

CURRIED POACHED FRUIT • SERVES 8 TO 12

1 lemon

One 2-inch piece ginger, peeled and sliced

½ cup granulated sugar

4 pears, peeled, cored, and thickly sliced

4 peaches or apples (depending on the season)*

1 cup pineapple, cut into ½-inch pieces

1 cup cherries, pitted, or ½ cup dried cherries

4 apricots, pitted and quartered, or ½ cup dried apricots

1 cup seedless green grapes

6 tablespoons unsalted butter

½ cup dark brown sugar

1 tablespoon curry powder

1. Using a vegetable peeler, cut strips of zest from the lemon (not including the white pith). Squeeze juice for the poaching liquid.

2. Make the poaching liquid by combining the lemon peel and juice, ginger, 4 cups water, and the sugar in a large saucepan. Bring to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer, covered, for 15 minutes.

3. Place the fruit in poaching liquid. If the liquid does not cover the fruit, gently push the fruit down to submerge it. Return the mixture to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer until the tip of a sharp knife can easily pierce the fruit, 5 to 10 minutes. (Since cooking time varies with the ripeness of the fruit, test frequently.)

4. Drain the fruit in a colander. Discard poaching liquid.

5. Preheat the oven to 300°F.

6. In a large skillet, melt the butter. Stir in the brown sugar and curry powder. Carefully fold in the fruit (so as not to mash it) with a plastic spatula. Transfer to a glass baking dish and bake for 30 minutes. Serve hot.

GEORGE WASHINGTON’S PUNCH This recipe came to us from the Reverend William Ralston. It was actually the Mount Vernon Christmas punch he got from Martha Washington Jackson, which she had from her aunt, Mrs. George A. Washington (Quennie Woods, who lived at Sewanee). They were both part of the collateral Washington family.

Father Ralston told us that he feels that the special thing about this punch is the way all those alcohols mix and blend. “It is as smooth as velvet,” he said. “It also does not leave you feeling ‘punchy’ the next day, although you certainly can drink too much of it. It also makes the base for the world’s best old-fashioned—add soda water and an orange slice. Divine! • SERVES A CROWD

1 quart strong brewed English Breakfast tea, sweetened

1 gallon good-quality bourbon

1 gallon sherry

1 quart sweet vermouth

1 pint best-quality Jamaican rum

1 pint yellow or green Chartreuse (I prefer green)

4 bottles champagne, or more to taste

12 lemons, each cut into 4 wedges

1 quart maraschino cherries, without stems but with their juice

Combine the first six ingredients. When it is time to serve the punch, add champagne—as much as you wish. Add lemon wedges and cherries to the punch and serve. (The punch is much improved if allowed to stand for at least 1 week before serving.)

An ice ring (made in a Bundt pan filled halfway with water and the cherries) looks good and helps keep the punch cold when serving.

*Dried fruit also can be substituted for fresh. If using fresh peaches, blanch the peaches in boiling water for 15 seconds. Peel and halve the peaches, remove the pits, and thickly slice. If using fresh apples, peel, core, and thickly slice.

When I first arrived in Beaufort, South Carolina, in 1961, I had never eaten an oyster, nor entertained any plans to do so in the future. Though I grew up surrounded by salt marshes and rivers, my mother had a landlubber’s disdain for all varieties of seafood, but held a special contempt for the lowly and despised oyster. I remember her wrinkling her nose as she held a pint of oysters aloft, saying, “I wouldn’t eat one of these balls of mucus in a famine.”

But we had come to the land of the great winter oyster roasts, where friends and neighbors gathered on weekends armed with blunt-nosed knives, dining on oysters that grown men had harvested from their beds at dead low tide that same day. At an oyster roast on Daufuskie Island thirty years ago, Jake Washington came up to me as I was devouring, with great pleasure, oysters he had gathered from the Chechessee River earlier that day. The afternoon was cold and clear, and I washed the oysters down with a beer so icy that my hand ached even though I was wearing shucker’s gloves. Among Daufuskie Islanders and folks from Bluffton and Hilton Head, there is a running argument about which river produces the most delicious and flavorful oysters: the Chechessee or the May River. I have partaken of both, and the sheer ecstasy of trying to make the subtle distinctions that make arguments like this arise makes me shiver with pleasure.

“You like those oysters, teacher?” Jake asked me. “They taste good?”

“Heaven. It’s like tasting heaven, Jake,” I answered.

“You know what you’re tasting, teacher?” Jake said. “You’re tasting last night’s high tide. Them oysters always keep some of the tide with them. It sweetens them up.”

Once when my boat broke down on the May River while going to Daufuskie, I drifted into an oyster bank and spent the hours awaiting rescue by opening up dozens of oysters with a pocketknife. Of all the oyster bars I have frequented in my life, none came close to the sheer deliciousness of those tide-swollen oysters I consumed that long-ago morning, which tasted of seawater with a slight cucumber aftertaste. The oyster is a child of tides and it tasted that cold morning like the best thing that the moon and the May River could conjure up to crown the shoulders of its inlets and estuaries. A raw oyster might be the food that my palate longs for most during the long summer season in Beaufort when we give our oysters their vacation time and they grow milky from their own roe. But then I remember my first roasted oyster, dipped in hot butter and placed on my tongue. As I bit into it, its succulence seemed outrageous, but it made my mouth the happiest place on my body. That first roasted oyster ranks high on my list of spectacular moments I have experienced while meandering through the markets and restaurants of the world—my first taste of lobster, truffle, beluga caviar, escargot, and South Carolina’s

mustard-based barbecue.

An oyster roast must take place on a cold day for it to work its proper magic. You should invite only those friends who have never heard of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. It is not a milieu that induces euphoria among highbrows and intellectuals. You’ll seldom hear talk about quantum physics or quadratic equations as newspapers are spread out over picnic tables. There will be a lot more pickup trucks than Lexuses in the parking lot, and the dress code is decidedly casual. The expectant hum of the crowd is what hunger sounds like. Great sacks of oysters are cut open with knives, and several men, who know exactly what they are doing, tend to an oak fire with a piece of tin laid over it on cinder blocks. It does not have to be tin, but it has to be a metal that will not melt into the fire. When the tin is iridescent and glowing from the fire, several men shovel bushels of oysters, many in clusters, onto the slab of tin and cover the oysters with wet burlap sacks.

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life

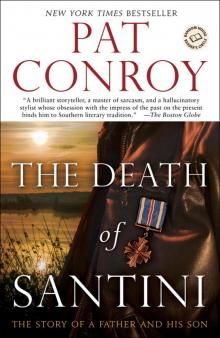

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son

The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son The Boo

The Boo The Prince of Tides

The Prince of Tides Beach Music

Beach Music The Water Is Wide

The Water Is Wide My Losing Season

My Losing Season The Lords of Discipline

The Lords of Discipline Pat Conroy Cookbook

Pat Conroy Cookbook My Reading Life

My Reading Life My Exaggerated Life

My Exaggerated Life The Pat Conroy Cookbook

The Pat Conroy Cookbook A Lowcountry Heart

A Lowcountry Heart The Death of Santini

The Death of Santini