- Home

- Pat Conroy

The Death of Santini Page 3

The Death of Santini Read online

Page 3

“I told you to shut up,” Dad said, then slapped me as I walked by.

“I will, Pat. That’s a promise,” Mom said. Dad slapped her in her face as my grandfather watched in wordless silence.

That night a fight between my parents rocked through the whole house. Five of us kids were watching TV in the basement when the screaming commenced. I went over and turned the TV off, then turned the lights out and said, “If Dad comes down here, pretend you’re asleep. Otherwise, he’ll start hitting.”

The shouting ended thirty minutes after it began; then the door opened at the top of the stairs and Dad turned on the lights and came halfway down the stairs. When he satisfied himself that we were all asleep, he shut the door noiselessly, so as not to wake us up. The next day, we left Chicago for Iowa as the end of my boyhood moved insanely on.

Dad drove his family to the blue-collar town of Clinton, Iowa, where another of his brothers, Fr. Jim Conroy, served as chaplain in the local Catholic hospital. Uncle Jim was a gregarious pink-faced man who grew temperamental when he was tired and was rumored to pick fights with every bishop he served under during his embattled career as a priest. He became famous for saying the fastest mass in the Midwest, and Catholics flocked to his services when he took over Holy Family parish in Davenport at the end of his career. In my lifetime of listening to lusterless sermons by Catholic priests, I knew Uncle Jim was famous for being the worst public speaker in the Iowa diocese. I never trusted him after he’d slapped me around for a nightmarish six weeks when I went on a fishing trip with him to Minnesota, and I made sure that none of my brothers went anywhere near him.

But I rode with Uncle Jim from his hospital to his home on the Mississippi River that would be the Conroy family home until our quarters were ready for us to move into at Offutt Air Force Base. Uncle Jim confessed to me that his brother Willie had called and begged him to get those seven kids out of his house.

“You guys really got on Grandpa and Grandma Conroy’s nerves,” Father Jim said. “They were driving Willie crazy complaining about the mess you were making.”

Uncle Jim drove across the Mississippi and turned north on a country road that paralleled the river, carrying us through beautiful Illinois farm country. We rode for twenty miles before he turned off to a dirt road, passed several farms, then pulled into the driveway of an insubstantial shack that looked both isolated and forlorn. The house sat on a hill above a tributary of the great river completely clogged with lily pads. You could fish all day and not get your hook wet.

When my mother toured the house, she erupted into another argument with Dad. “This is just great, Don. You’re going to leave your wife and seven kids in this run-down dump with three beds, one toilet, no air-conditioning, no car, no stove, in the middle of goddamn nowhere. Real good thinking, Don. Great planning,” she said, unhinged and wrathful. “There is no TV set, no radio, not a toy for the little kids to play with, not a bottle of milk or a loaf of bread or a jar of peanut butter. Jim, what were you thinking, having us here?”

“Not much, Peggy,” Uncle Jim said. “I’ve never had a family. I just didn’t think it through.”

Dad said, “Okay, kids. Attention to orders. Start getting this place polished up. There’ll be a formal inspection at fifteen hundred hours.”

Of all the disconsolate summers the Conroy family spent following our Marine from base to base, everyone agrees that our summer on the Mississippi River was the most soul-killing of all. We sweltered in a summer heat that was brutal, and the house was so small and inadequate for our tribe that we stumbled over one another and got in each other’s way from morning till night. In the mornings, we woke with nothing to do, and went to sleep because there was nothing to do at night, either.

Uncle Jim was solicitous and as helpful as he could be and provided our only lifeline to civilization and to groceries. Several times a week he would take us all for a swim at a public lake in a nearby town. It was the summer I thought my mother’s mental health began to deteriorate, and I think my sister Carol Ann suffered a mental breakdown caused by that ceaseless drumbeat of days. Carol Ann would turn her face to the wall and weep piteously all day long. Mom appeared sick and exhausted and slept long periods during the day, ignoring the many needs of my younger siblings. The days were interminable and Mom grew more weakened and distressed than I had ever seen her. I asked what was wrong and how I could help.

“Everything!” she would scream. “Everything. Take your pick. Make my kids disappear. Make Don vanish into thin air. Leave me alone.”

• • •

In July I got a brief respite when I took a Trailways bus on a two-day trip to Columbia, South Carolina, to play in the North-South all-star game. I’d not touched a basketball since February, was out of shape, and played a lackluster game when I needed to have a superlative one. After the game, Coach Hank Witt, an assistant football coach at The Citadel, the military college of South Carolina, came up to tell me that I had just become part of The Citadel family, and he wished to welcome me. Coach Witt handed me a Citadel sweatshirt and I delivered him a full, sweaty body hug that he extricated himself from with some difficulty. In my enthusiasm, I was practically jumping out of my socks. By then, I’d given up hope of going to any college that fall and had thought about entering the Marine Corps as a recruit at Parris Island because all other avenues had been closed off to me. My father never told me nor my mother that he had filled out an application for me to attend The Citadel. I danced my way back into the locker room below the university field house and practically did a soft-shoe as I soaped myself down in the shower. In my mind I’d struggled over the final obstacles, and there were scores of books and hundreds of papers written into my future. Because I’d been accepted at The Citadel, I could feel the launching of all the books inside me like artillery placements I’d camouflaged in the hills. The possibilities seemed limitless as I dressed in the afterglow of that message. In my imagination, getting a college degree was as lucky as a miner stumbling across the Comstock Lode, except that it could never be taken away from me or given to someone else. I could walk down the streets for the rest of my life, hearing people say, “That boy went to college.” And then it dawned on me that the military college of South Carolina did not preen about being a crucible for novelists or poets. Hell, I thought in both bravado and innocence, I’ll make it safe for both.

I returned to our exile on the Mississippi with great reluctance and thought Mom looked even more haggard and spent. She looked like a sleepwalker going through her morning chores. I was still disturbed by her appearance when Dad rang the house for his weekly phone call.

“I’m worried about Mom,” I said, trying to sound every inch the adult. “She doesn’t seem to be herself. She’s totally exhausted.”

“Worry about something you can do something about, pal. Give your mother the phone. You’re wasting my time and money.”

“Hey, Mom,” I yelled to her in the grassless yard. “Dad’s on the phone.”

It was the summer I tackled some of the great Russian novelists, such as Dostoyevsky and Turgenev. I entered the soul of Russia while swinging in a hammock with the Mississippi River visible in the distance. Mom and Carol Ann read The Brothers Karamazov after I did and I remember discussing the book and what it meant to us. We were breaking camp and moving into our new quarters in the middle of August. Not one of us looked back at that miserable cottage when we left it; nor did any of us ever see it again. We had been banished there for two months, and none of us remembers having a good day there in rural Illinois during the summer that never seemed to end.

It was two weeks before I left for The Citadel when we moved into our new house on Offutt Air Force Base. Mom took me to the PX to buy the socks, underwear, T-shirts, and military shoes The Citadel required. Dad had given me his trunk, which he had taken with him to World War II. Before my grand departure, my mother took me out to the officers’ club for lunch, which she had never done before. It was the first time I ever co

nsidered how a mother must feel when her oldest child goes off to college. It seemed like some essential rite of passage that moved me more than I could express to her. I don’t think I would have survived my trial by father had she not been there every step of the way. I tried to tell her how much she meant to me and how I adored everything about her. I told her I wanted to do things in the world that would make her proud to be my mother.

My mother took my hand and said that I’d made her proud already. I had survived Santini and provided a great example to my younger brothers and sisters. Then she told me a secret she had kept from the rest of the family. She had just discovered that she had cancer and had to have a massive hysterectomy sometime in the near future. There was a real possibility that she would die on the operating table. She wanted me to promise her something. I told her I would promise her anything, and would fulfill that promise.

My mother said, “If I die because of the operation, Pat, I want you to promise me you’ll quit The Citadel and come home to raise your brothers and sisters. I’m afraid your father would end up killing them all.”

“He may start off with me,” I said.

“He thinks you’re a match for him,” she said.

“Not yet. But I’m getting there, Mom.”

“Then promise me.”

“If you die,” I said, starting to cry just mentioning the words, “I’ll quit The Citadel and come home to raise my brothers and sisters.”

“Get Tim and Tom in high school,” she said, “and then you can start your life all over again.”

“I promise,” I said, through tears.

On September 2, 1963, I left the city of Omaha by train to walk into the fearful mouth of The Citadel’s plebe system. Even my father had not prepared me to encounter such ferocious abuse. I hated it from the moment I walked into the barracks until the time the upperclassmen recognized me the following spring. It was a nightmare from beginning to end, and I found nothing ennobling about it. I’d been brought up in the United States Marine Corps and my military education was complete the day I entered the barracks. In the Marines, you fed your men first, and then the officer in charge ate only after his men were fed. At The Citadel, the cadets hounded and brutalized and starved the plebes. The Romeo company cadre was especially savage and feral. I’ve not quite found it in my heart to forgive them almost fifty years later.

As a novelist, however, I thought I was blessed with my Citadel education. It gave me wider knowledge of the nature of atrocity and mankind’s capacity for infinite cruelty. I believe The Citadel plebe system prepared me quite well for the setbacks and disappointments of life—it even prepared me for the savagery and jealousies of my brother and sister writers. It gave me a narrative of darkness that I could move through my life’s work. It gave me a story line that was action-packed and adrenaline-fueled, since my plebe system was not like your day in the eating clubs of Princeton. I’ve ended up writing about my college as much as any writer in American history. It became my crucible of origin, whose anthems were all warlike and barbarous and wild. I’d been tested by American males as few writers had ever been, and I was the handiwork of the school’s grim codes. They sensed my weakness, my disabling emotional frailty, and they hardened me into the likeness of themselves, made me pretend to be one of them. It took me many years to understand I was actually one of them. It took The Citadel much longer to accept me into its own staunch brotherhood.

Soon after I entered college, my mother was operated on for her hysterectomy, and the doctors made a mess of it. As she predicted, she almost died on the operating table. For a long, agonizing month, she was in the hospital with her life in danger the whole time. I would have been frantic but the plebe system was giving me more than I could handle and I was fighting for my survival every day. When I went home to Omaha on the Christmas break, Mom was there, but I was anxious about her and asked Dad so many questions about her health that I annoyed him.

“Hey, you her doctor, sports fan? She’s fine. She’s still a little weak, but she’s getting there,” Dad said.

When I burst through the door in my excitement to see my family, I did what I had done since I was a five-year-old boy and went down on one knee to receive the delirious charge of the Great Dog Chippie, who would fly into my arms. This time there was no charge; there was nothing to pet; there was no Great Dog Chippie.

Mom came out of the kitchen to watch me and said, “I had to put the dog down. It was for the best.”

I hugged my mother furiously and kissed her a dozen times. She pushed me back, rather brusquely, I thought, and looked at me with eyes I did not recognize and said in a voice that was not my mother’s voice, “You can sleep downstairs in the basement with Mike, Kathy, and Jimbo. You don’t have a bed now, Pat, so we borrowed one for you.”

“What do you mean, I don’t have a bed?”

“You don’t live here anymore,” she said.

Somewhere during the course of that hysterectomy, in the scrimmage of blood and hormones and the great shock of estrogen shutdown that my mother suffered during her morbid ordeal, I had lost part of the mother who raised me, the sweet girl, the smiling one. She had left part of herself on that operating table and a darker Peg Conroy made her way forward in the world, an angrier one, and I think a more treacherous one. My brothers and sisters fight me on this and say that Mom always was the same mother she was in the end. Though hormonal mysteries have always been beyond the realm of my understanding, I still hold to the claim that there was a significant change in my mother’s personality after her operation. My brothers and sisters hoot in derision over this and accuse me of worshiping a mother who was my own creation or invention. My version of Peg Conroy rings hollow and untrue to them, and they’re not shy about letting me know it. To them she was vain, cheap, and had grown bone-tired with the exhaustion of motherhood.

In despair, I flew back to The Citadel to complete my abysmal plebe year. That was my job now and I was going to do it. But I faced it with a damaged mother and a Chippie-less world I could never repair.

CHAPTER 2 •

Fun and Games at The Citadel

After the holidays, I left the city of Omaha yet again for a two-and-a-half-day journey back to Charleston. Liberated from my father’s house at long last, I felt my adventure in life had finally begun. During the train trip, I entertained extravagant fantasies of becoming a writer. I pretended I was the young Thomas Wolfe gorging on the images of small towns and cornfields as I returned to the South. I wrote an earnest poem about two-stoplight villages. As passive as a lamb, I was traveling back to a slaughterhouse for boys, where I would have to kill the poet in me as an act of survival. I’d never encountered another college student who was as mismatched and insufficient for the test of his chosen college. Though I was heroically unprepared for my immersion into this final, unsurpassable test of manhood, The Citadel was my only chance to earn a degree, and I planned to make the most of it.

When I entered The Citadel in the fall, I thought I was going to college. This delusion was quickly dispelled. What I entered was the plebe system. I hated it from the moment I walked into the barracks. Even my father had not prepared me for such ferocious abuse. What I hadn’t factored in was the peerless cruelty of the training cadre. That the plebe year would prove its worth as an inflammable touchstone, a worthy successor to my father’s trial by fire, came as a great surprise to me. I thought I’d endured the great tempestuous tests of manhood by surviving my father’s fists and becoming a letterman in every sport I participated in during high school. I had forged my soul in a fire pit of cruelty and discipline and was not expecting those darkling, black winds that The Citadel threw at me for the next four years. Desperately, I wanted to be a writer and didn’t see how my immersion into the annihilating white noise of suffering was going to help me in my quest.

Though I survived the plebe system, I did not distinguish myself during that rite of passage. For the first three months, I lived in terror that my mother mig

ht not recover from the botched hysterectomy that had her lingering near death for several days. On the rare occasions I was allowed to call home, I talked to Stanny, my maternal grandmother, who was often drunk and lugubrious as she reported on my mother’s condition. “Yo’ mama’s dying and that’s the honest truth, Pat,” she’d say to me. “You might as well quit that school and come home to raise your brothers and sisters. You’ll be doing it sooner or later anyhow. She’s getting weaker every day. Pray hard for your mama, Pat. She’s not going to make it. Our girl’s dying, son, just dying.”

Then Stanny would hang up or pass out with the phone in her hand, and I would sit in a phone booth shivering with despair. My future was all paralysis and grief to me. The plebe system had gotten the better of me, and my time on the basketball team brought me close to a physical breakdown. I was not strong enough to face a world without Peg Conroy. I staggered my way toward June.

The cadre tried to turn me into a mirror image of them, and they trained me to torture plebes as they had molested me and my classmates. When I was going to sleep at night, I promised that I wouldn’t model myself after a single member of Romeo company. If I ever led a platoon or squadron, I planned for my men to love and respect and follow me. They would eat before I ate and sleep before I went to bed. I would try to be more courageous in battle than I asked them to be. My battalion who loved me would slaughter your battalion who hated you was the summation of my military philosophy long before I entered the gates of The Citadel. I developed that philosophy as the son of the Marine Corps because I knew many Marines who hated serving with my father. The Citadel’s plebe system taught me nothing about leadership and everything about humiliation. It was never to be for me, then or now. I was not one of them.

I did discover, however, the joys and mysteries of The Citadel’s library, which for most cadets was as remote and undiscoverable as an oasis below the Atlas Mountains. For four years, I would enter the library and find a welcoming world of solitude and books awaiting my inspection, and in their mute attentiveness, I heard those same books trying to call out my name as I wandered through their marvelous stacks at my leisure. There, at the Daniel Library, I found the college education I was looking for, and I would carry piles of books across the parade ground at night, and bring back the books I’d finished reading the next afternoon. Without my knowledge, the faculty wives began to call me “the boy with the books,” even though they couldn’t put a name to my face until I began to play well as a basketball player. In the classroom, my English teachers were all Southern white men both conservative and kindly, but they were helpful in my attempt to become a writer and did everything they could to nurture that uncommon ambition in a member of the Corps of Cadets. When I wrote drivel, they claimed it showed promise. When I wrote with mediocre results, they calmly instructed me to make it better with more of an eye toward craft. When I turned in something good, they told me I was on my way. They never slapped me down or ridiculed me or heaped derision on me, because I believe they saw the impossibility of the task I’d set up for myself. Col. John Doyle wanted me to be “The Citadel’s Faulkner.” Col. James Carpenter chose Dickens for my emulation. James Harrison wanted me to shoot for a slot near Henry James. As impossible as those goals were, I learned that it is lovely for a writer to receive such validation at so young an age by the men who led him or her by the hand to an appreciation of the world’s greatest novelists. Every day I found myself thrust into a building of fifty thousand books famished for readership. By slow degrees my writing was getting better, more hard-nosed and less abstract. It was plain to me I lacked genius when it came to my ambition to write books, but I could ingest all of the writings of those born with the gift.

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life

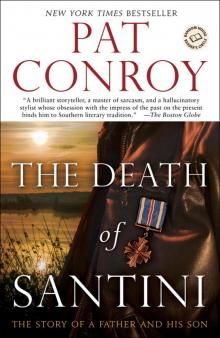

A Lowcountry Heart: Reflections on a Writing Life The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son

The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son The Boo

The Boo The Prince of Tides

The Prince of Tides Beach Music

Beach Music The Water Is Wide

The Water Is Wide My Losing Season

My Losing Season The Lords of Discipline

The Lords of Discipline Pat Conroy Cookbook

Pat Conroy Cookbook My Reading Life

My Reading Life My Exaggerated Life

My Exaggerated Life The Pat Conroy Cookbook

The Pat Conroy Cookbook A Lowcountry Heart

A Lowcountry Heart The Death of Santini

The Death of Santini